21 September 2022

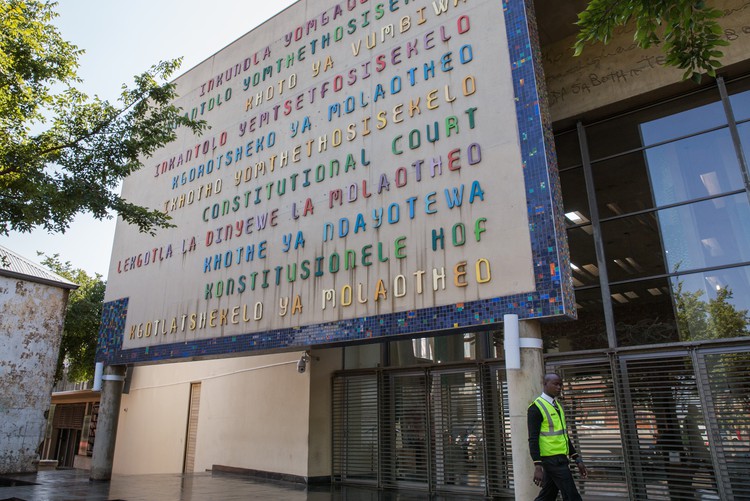

The Constitutional Court has ruled that sections of the Copyright Act are unconstitutional and Parliament has 24 months to fix it. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Blind and visually impaired people, prevented from converting written material to braille or other accessible formats without the permission of copyright holders, can now do so following a ruling by the Constitutional Court.

The court has also given Parliament 24 months to cure the “unconstitutional” defects in the Copyright Act.

In a unanimous decision on Wednesday, the Constitutional Court ruled that the Copyright Act is unconstitutional in that it limits the access of visually impaired people to published literary works and artistic works.

Before the court was a ruling by Gauteng High Court Judge Mandla Mbongwe, made almost one year ago, that the provisions, which imposed a “book famine” for blind and visually impaired people, were an unjustifiable limit to their rights and did not pass constitutional muster.

While Judge Mbongwe ruled that the Act’s gatekeeping provisions, enacted in 1978, would no longer be effective from the date of his ruling, this had to be confirmed by the Constitutional Court.

In May, the court heard argument in the application launched by Blind SA, represented by SECTION27, against the Minister of Trade, Industry and Competition.

Amendments to the Act have been in the offing for some 12 years.

Blind SA’s advocate Jonathan Berger argued during the hearing that an amendment bill, which would exempt visually impaired people from its provisions, had been “held hostage” to a lengthy legislative process.

In the meantime, he said, many South Africans including people such as retired Constitutional Court Judge Zac Yacoob and Spotlight Editor Marcus Low, struggled to access books to learn.

Berger argued that when permission was sought to convert the written material to an accessible format, it was “either refused, or worse, just ignored with no reasons given”.

The Minister did not oppose the application, conceding that the Act was unconstitutional and the order sought was in line with the amendment bill, currently in the legislative process.

While giving Parliament 24 months to “cure the defect” in the Act, the Constitutional Court ruled that in the meantime certain exceptions would apply to those affected. Those affected included government institutions and non-profit companies which provide education and training, and caregivers. The court ruled that they must have access to written works in an accessible format without prior authorisation.

It spelt out that this order affects people who are blind, or have any visual impairment and are unable to read printed works, or who cannot hold or manipulate a book, or focus or move their eyes.

The Minister was ordered to pay Blind SA’s costs.

Writing on behalf of the court, Acting Judge David Unterhalter said the affidavits of those affected “speak trenchantly of the deprivations wrought upon persons” because of the provisions of the Act.

One, a Mr Gama, a teacher at a school for the deaf and blind, had described how many special schools across the country struggled to obtain sufficient textbooks in accessible formats. This disadvantaged learners and impaired their dignity. After learners leave school, their position is often worse still.

Judge Unterhalter repeated the words of Justice Yacoob, who said: “My own experience tells me that it is impossible to express in words how urgent this is. The best I can do is say that every day that the present Copyright Act prevails in the form in which it is, literally thousands of blind and visually impaired people are deprived of reading material and the prejudice to them is irreparable, incalculable and very difficult to put in words.”

Judge Unterhalter said it took little imagination to appreciate what the scarcity, relative or absolute, did for the life chances of those with these disabilities, and that some had achieved substantial success was only testament to their personal fortitude.

While the requirement of authorisation protected the rights of copyright owners, regard needed to be had on its impact and the challenge by Blind SA was “well founded”.

“No case was advanced by the Minister to show that the limitation of rights is justified. Indeed, the minister did not oppose the application.”

Judge Unterhalter said the parliamentary process had already taken too long, and those affected should not have to wait further to secure a remedy. Interim relief was therefore appropriate during the 24-month period of suspension.

Regarding submissions that South Africa should ratify the Marrakesh Treaty to Facilitate Access to Published Works for Persons Who Are Blind, Visually Impaired or Otherwise Print Disabled, which would increase the number of books available, he said this was a matter for Parliament and not the court.