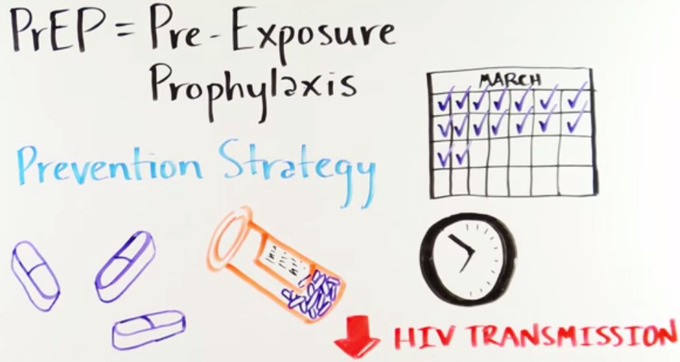

An antiretroviral pill for sexually active HIV-negative people reduces the risk of contracting HIV. Image from Demystifying HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (Creative Commons License).

9 March 2016

Last year the Medicines Control Council approved a daily antiretroviral pill for HIV-negative people to reduce their risk of contracting HIV. This is called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP.

But the pill, which consists of the drugs tenofovir and emtricitabine, and is better known by one of its brand names, Truvada, is not yet available for this purpose in public health facilities. The Department of Health is still drafting guidelines on its use.

After years of research, this pill is in practice the only PrEP option. Many devices and gels have been tried, but with limited success at best. For example, a couple of weeks ago a study that tested a vaginal ring showed that while it was not ineffective, the results were not good enough to justify making it widely available.

Marcus Low of the Treatment Action Campaign says PrEP “will likely only become available [in public facilities] once the Department of Health finalises and publishes guidelines … We understand that the Department of Health is working on these.”

Some questions arise when considering the state-sponsored scale-up of prep. Will it be effective enough for women in South Africa? Who should take it? What will it cost? And should it be an HIV prevention priority?

A number of clinical trials have been conducted on PrEP, which have shown it to be effective when people adhere (when they take the medicine nearly everyday). Results among gay men have been much better than among women in sub-Saharan Africa.

Professor Quarraisha Abdool Karim is an epidemiologist who is the Associate Scientific Director of CAPRISA, and has been a leading researcher on PrEP. She says there is a “consistent body of evidence indicating the protective benefit of daily Truvada or tenofovir alone”. But, she explains that adherence is very important for it to work, especially in women, because there “appears to be a higher threshold of drug levels required” in women.

Abdool Karim says while some clinical trials in women have shown that PrEP protects women from HIV, and others have not, what is consistent is that it is effective if the pills are taken.

Dr Kevin Rebe of the Anova Health Institute says that evidence for efficacy with PrEP is highest for men who have sex with men. He explains that PrEP “takes about a week to build up levels in rectal tissue to prevent” contracting HIV through anal sex. “But it takes up to 30 days to build up in vaginal tissues and provide protection.”

While PrEP has been around for a while in Europe and US, there has been “limited experience and local data” in South Africa to support its use. This is according to Dr Oscar Radebe who is a clinical manager at Health4Men.

Radebe said that in the private sector very few GPs prescribe PrEP and those who do have “limited expertise in managing a patient on PrEP”.

If the Department of Health makes PrEP available in the public health system, it is not clear who should be targeted. Sex workers, men who have sex with men, people without HIV whose partners have HIV, people in the long-distance transport industry and prisoners are just some groups at high risk of HIV.

Rebe suggests that because the evidence for PrEP’s effectiveness is best for men who have sex with men perhaps this group along with sex workers should be targeted early. “Adolescent girls and young women are [also] a very high risk population for HIV … and may benefit tremendously from access.” Unfortunately, he says, the evidence for how to roll out PrEP to women in this population group is lacking.

But Abdool Karim suggests that aiming PrEP at particular groups is the wrong approach because it will “stigmatise PrEP use”. She says it may be better to make it available “to those who want to use it as part of combination prevention and let those who need to protect themselves choose what they want to use. We know that the more options people have the more likely they are to use the option that works best for them at a point in time.”

Professor Francois Venter of the Wits Reproductive Health & Research Unit believes that most South Africans who are sexually active are “at risk”. He says that there needs to be careful evaluation of whom PrEP is offered to. “We need people who have a reasonable HIV risk, who will take the tablets, so as to balance the risk of HIV against the cost and small risk of toxicity.”

In the private sector the cheapest generic version of the PrEP pill we could find costs R340 per month. The public sector currently buys the drug for HIV treatment for R69 per month. If, say, one million people take up PrEP in the public sector, the PrEP drug bill for the Department of Health will be about R828 million a year at the current price. Of course, prices change with demand and currency fluctuations.

While PrEP used consistently is effective, studies show that giving antiretrovirals to people with HIV is even more effective at preventing transmission. This reduces the amount of virus to undetectable levels in their bodies, so that they are no longer infectious. Also, new World Health Organisation guidelines recommend treating all people with HIV for their own benefit. So providing antiretrovirals to people with HIV has both a treatment and prevention benefit.

Low of TAC says, “The more urgent need in South Africa is to make sure that all people who are already living with HIV can access treatment. Currently more than three million people living with HIV in South Africa are not taking treatment”.

Nevertheless, there might be room for both options, if the Treasury can find the money, or if PrEP is limited to people at the highest risk of HIV infection.

Abdool Karim says there is need for both treatment and PrEP. “We are still seeing large numbers of new infections and deaths. Our responses need to address both.”

Update: The government has announced that all sex workers in South Africa, irrespective of their HIV status, will be offered antiretrovirals. This means PrEP for HIV-negative sex workers and treatment for HIV-positive sex workers.

Here are some of the clinical trials that have tested PrEP.

The iPrEx study included gay men and transgender women. In the study, the HIV infection rate of people assigned to take PrEP was 44% lower than those who were not. Results were even better for participants who took the pill more than nine days out of of ten: they were 73% less likely to contract HIV than people not on PrEP.

The Partners Study was conducted on heterosexual couples where one partner was HIV-positive. The results showed that the risk of infection was reduced by 75% for people on tenofovir/emtricitabine.

In a trial called VOICE, where all the participants were women, results were less promising: there was no statistically significant difference in prevention between people who took PrEP and those who did not. Many participants assigned to take PrEP did not actually take the drug. Adherence was particularly poor for young, unmarried women – one of the most at-risk groups.