Who inherits your partner’s estate if you’re not married?

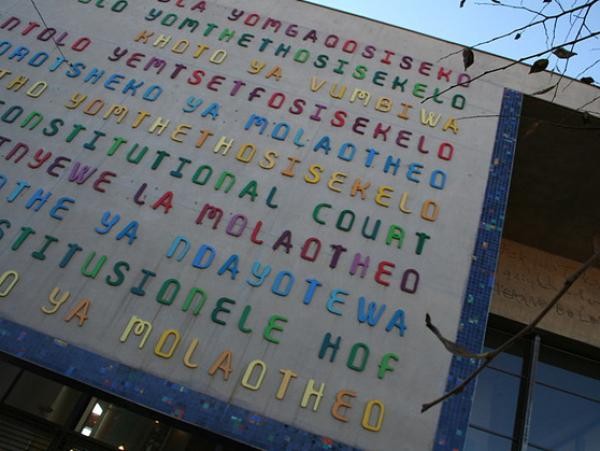

Constitutional Court will soon give us an answer

Last Thursday, the Constitutional Court heard an application for leave to appeal. The case involved a gay couple Mr Laubser and Mr Duplan, who lived together but never married. Mr Laubser passed away without having drawn up a will.

The question to be decided is whether, following the death of his partner, Mr Duplan could inherit as a spouse under the Intestate Succession Act. The case received extensive coverage that placed emphasis on the sexual orientation of the couple but this actually is not the first time this issue has come before the court.

The Constitutional Court has decided on the issue of whether unmarried life partners may inherit twice before.

In fact, the issue as it relates to same-sex couples was previously decided in the case Gory v Kolver. In the Gory case, the court held that the definition of the word ‘spouse’ included same-sex life partnerships, even if this partnership was not formalised by marriage. As a result, same-sex life partners could inherit as though they were legally the deceased’s spouse where there was no will.

The issue above is clearly the same as the case before the court now.

Mr Laubser was in a permanent same-sex life partnership with Mr Duplan and they supported each other during that time. Their partnership began in 2003 and continued until Mr Laubser’s passing in 2015. At the time of Mr Laubser’s death, the partnership had not been formalised as a civil union and Mr Laubser did not leave a will.

When someone dies and does not leave a valid will, the Intestate Succession Act applies. The Act, in simple terms, divides a deceased’s estate between family members and spouses. It only applies when there is no valid will.

Typically, the biggest portion of the estate (if the estate is small) will go to a spouse and then equal amounts are distributed to the descendants. However, where there is no spouse or descendants, the estate will go on to be divided between living family members according to the rules in the Act.

The decision in Gory allowed partners in same-sex life partnerships to be considered spouses for the purposes of the Act which, in turn, allowed them to inherit.

When the High Court decided on the Laubser case, the extended definition from Gory was applied to find that Mr Duplan be treated as a legal spouse and was entitled to inherit a portion of Mr Laubser’s estate, despite them never having married. Mr Laubser’s brother, who was executor of the estate and stood to inherit everything if Mr Duplan could not, appealed the decision directly to the Constitutional Court.

The Constitutional Court receives thousands of applications and petitions for leave to appeal and cannot afford them all a hearing. Where the matter is of importance or in the public interest, the court will prioritise hearing it.

In the case of Laubser N.O. v Duplan the High Court applied the law of a previous Constitutional Court case to facts that were almost identical. There doesn’t seem to be any reason to reconsider this issue again because there is nothing new in this case.

This raises the question: why is the Constitutional Court hearing an application in a matter which has already been decided on?

The short answer is that the Civil Union Act, which allowed same-sex partners to marry, wasn’t in force at the time Gory was decided. As a result, it wouldn’t have been possible for same-sex couples to get married. The decision in the Gory case was an attempt to afford same-sex couples the same protections and privileges afforded to hetereosexual couples since same-sex couples were discriminated against at the time.

Does the Civil Union Act change anything?

It is at this point that the case of Volks v Robinson becomes relevant. The Volks case is another important case concerning the definition of spouse under the Intestate Succession Act but unlike Gory, the case involved an unmarried heterosexual couple in a life partnership.

The court found that the surviving partner could not be included under the definition of spouse since the couple had the option to formalise their partnership but had chosen not to. The couple could not be entitled to the protections afforded to married persons if they chose not to marry.

Given that the same reasoning could apply to same-sex couples following the Civil Union Act, it is easy to see the argument that same-sex couples are now given greater protections than heterosexual couples when it comes to interstate succession for unmarried life partners.

This argument, loosely speaking is what the executor has chosen to adopt in contending that the order in Gory was an interim measure that fell away when the Civil Union Act came into force. If the court agrees with this argument, same-sex couples will only be considered spouses if they enter into a civil union.

It is unlikely that the court will find these arguments convincing given that it was argued that the extra protection for same-sex couples were open to abuse. The order including unmarried same-sex life partners in the definition of spouses has been around for the better part of eight years and practically speaking, intestate succession still functions without problem.

Does that mean that the Gory decision should be allowed to stand?

The Commission for Gender Equality advanced arguments as an amicus curiae (friend of the court) which centred around two issues. The first is that including unmarried same-sex parties in the definition of spouse promotes substantive equality.

The second issue raised, and the one of greater significance, concerns the recognition of domestic partnerships. This recognition is supported by international definitions of family relationships. The Commission stressed that we should not favour certain kinds of families over others.

This is an interesting lens through which we can examine the Gory decision since it is not just same-sex couples who choose not to formalise their partnerships. Many people in South Africa choose not to formalise their life partnerships but form familial and romantic bonds akin to marriage. In fact, in 2009, the Domestic Partnerships Bill was published for comment. The bill sought to legally recognise domestic partnerships but was ultimately never tabled in Parliament. As a result, domestic partnerships exist in a legal limbo of existing but not being recognised.

Perhaps the issue before the court is not whether the Gory decision favours same-sex couples but rather whether unmarried life partners deserve protection equal to married partners, irrespective of sexual orientation.

The Court reserved judgement in this matter so, for now, unmarried partners are best advised to draw up wills to protect their partners now rather than risk the uncertainty.

Next: Disabled man fetches water with a bucket tied to his crutches

Previous: South Africa’s 2016 municipal elections – why the excitement?

© 2016 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.