18 June 2020

This is issue 7 of Covid-19 Report. We point you to the latest quality science on the pandemic. If you come across unfamiliar terms, there is a glossary at the bottom of the article.

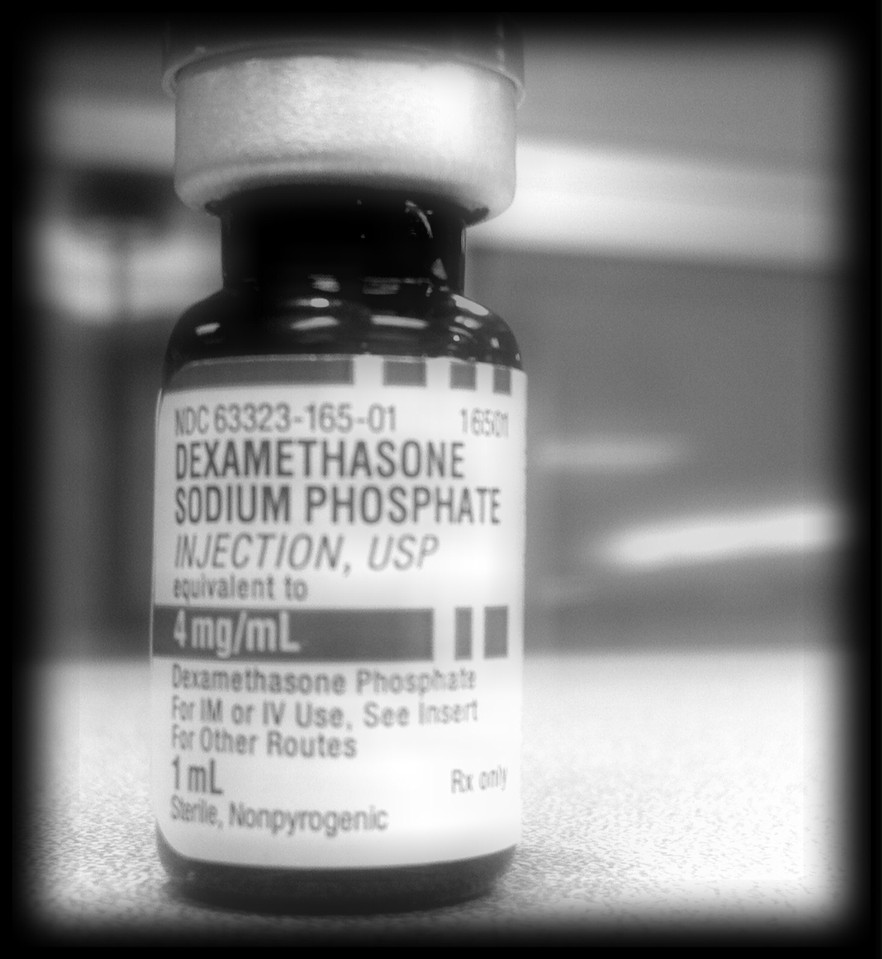

A randomised controlled clinical trial, Recovery, has found that the steroid dexamethasone reduces the risk of death.

In this UK study, at 28 days the death rate of the 4,321 patients receiving “usual care alone” was 41% for those who required ventilation, 25% for those requiring oxygen only and 13% for those who did not require any respirator intervention.

But for the 2,104 patients who received 6mg of dexamethasone once a day for ten days, deaths were one-third lower than the “usual care” ventilated patients and one fifth lower than the “usual care” patients who were receiving oxygen only. There was no benefit for patients who did not require respiratory support.

This is the first properly conducted Covid-19 trial to show that a drug has a life-saving benefit.

Some cautions: This is far from a silver bullet; mortality remains extremely high. The data has not yet been published and the results are not yet peer reviewed. Many doctors are rightfully nervous after a spate of bad studies that have dominated news headlines during the epidemic. Nevertheless this is promising.

The positive result is not entirely expected. There was an early warning in February that steroids should be avoided in the treatment of Covid-19 patients, in part because they appear to have performed poorly in the treatment of SARS and MERS, the two previous coronavirus epidemics this century.

The drug is not too expensive: a pack of ten 4mg injections (not quite the right dose) is priced at less than R150 in the private sector. By contrast remdesivir, a drug that has been found to reduce the length of Covid-19 illness, is not yet generally available in South Africa and is expected to be priced much higher.

Another promising drug to look out for is mavrilimumab. A preliminary study published in The Lancet found that people taking this drug have better outcomes. But a randomised clinical trial is needed to confirm this result. Perhaps the future of Covid-19 care will involve a cocktail of drugs.

It’s unfortunate that a drug, because it was hyped by at least two presidents and some doctors, has become so politicised. The water was further muddied by a highly publicised observational study published in The Lancet which showed no benefit, perhaps even harm, from hydroxychloroquine, followed by the even more highly publicised retraction of that article.

But as explained in this article in Science, “[T]hree large studies, two in people exposed to the virus and at risk of infection and the other in severely ill patients, show no benefit from the drug”. Most trials of the drug have now been stopped. The article points out that there is still a good case for continuing to test whether the drug can “prevent infection if given to people just in case they get exposed to the virus, for instance on the job at a hospital”. It’s also possible that the drug may be found to be effective when combined with other drugs, but we’re not holding our breath.

Much has been written about the retraction of the hydroxychloroquine study in The Lancet as well as a study by the same authors in the NEJM (both studies were described in previous issues of Covid-19 Report). The retractions are the highest profile example of bad science during a pandemic that has spawned a great deal of poor quality research. An analysis of the problem published in AIM is worth reading.

An article in The Guardian suggests ways to improve the peer review system. The Lancet’s editor Richard Horton has emphasised that the peer review system is dependent on trust and honesty, and that it cannot work otherwise. This is true but there are nevertheless several changes that can be made to the system to reduce the risk of publishing deeply flawed research in leading journals. Here are four:

The official Covid-19 death toll is now over 450,000, but this is a considerable underestimate. An ongoing Financial Times analysis shows that excess deaths in many European countries far exceed their Covid-19 official death tolls. Official death figures from many, perhaps most, countries, such as Russia, are not even in the ballpark. Only conspiracy theorists can at this point compare Covid-19 to seasonal flu. Here is a useful analysis in Nature of the risk of dying if infected by SARS-CoV-2. There is still great uncertainty. It also differs substantially by geography, influenced by age and health of the population, quality of the health system and whether hospitals get overrun. A rough estimate is that the overall risk of dying if infected, including asymptomatic cases, is 0.5 to 2%. There’s also considerable morbidity for many people who don’t die of the disease.

A model in The Lancet estimates global, regional and national numbers of people at risk of severe Covid-19 because of underlying health risks. The authors estimate that 1.7 billion people (22% of the world population) have at least one condition putting them at increased risk of severe Covid-19. It estimates that 349 million people are at severe risk of hospital admission if infected.

So how is South Africa doing? We are still in the early stages of our epidemic. The weekly MRC mortality report is helping us understand the effect of both the lockdown and the epidemic. It now includes data up to 9 June but the writers of the report have placed a big warning at the top of it:

“The Department of Home Affairs is facing sporadic temporary office closures, particularly in areas that are more affected by Covid-19. This may affect our allocation of a death to a metro area. For example, a death that occurred in the City of Cape Town might have been registered at an office outside of the City because of the temporary closure. Closure may also cause a delay in the processing of the death registration which would result in an underestimate of the deaths in the most recent week.”

Despite this we learn the following from the latest report:

The Western Cape government has published data on factors associated with Covid-19 deaths. A worry has been whether TB or HIV increases the risk of dying of Covid-19. The answer seems to be yes, but not nearly as much as diabetes or old age. There’s an excellent summary of this data on HIV i-Base.

Doctors we’ve spoken to have stressed that they are seeing many obese people in their wards often with poor outcomes. Unfortunately there is not yet any published South African data on this.

Beyond the statistics this is a poignant description in the NEJM of the unique difficulties patients, doctors and families face because of Covid-19. In AIM a doctor describes her experience facing death.

And this dispatch by UK doctor Rachel Clarke is a devastating portrayal of the death of a patient as well as an indictment of her government.

South African doctors have explained in the SAMJ why disinfection tunnels are a very bad idea.

Also in the SAMJ doctors suggest the need for clinical trials using blood plasma from recovered patients in the hope that their antibodies will protect people who become infected. This is a potentially promising treatment option to look out for but it’s very early days.