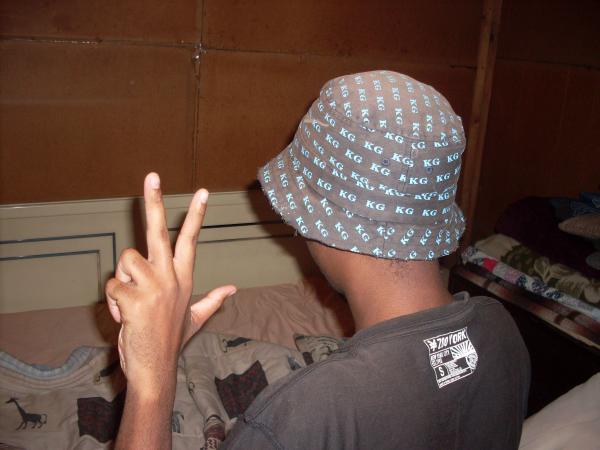

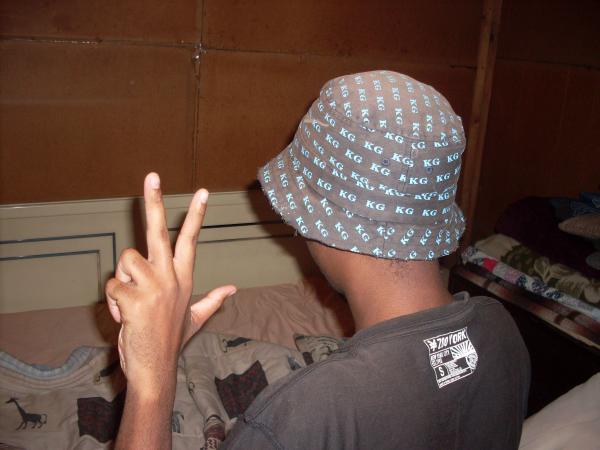

A member of the Vatos holds up a sign used by the gang to identify and greet each other.

18 April 2012

“We are fighting for our freedom, our freedom to go anywhere we want to go in Khayelitsha,” says Latinyo, an 18-year-old grade 12 learner from Khayelitsha’s H-section. He has been involved in gangs since the age of 12 and says he has lost count of how many murders he has committed.

19-year-old Abosh and 18-year-old Analito are both in grade 11 and are Latinyo’s second and third in command. All three boys use pseudonyms and are members of the Vatos Locos gang.

They say that they are fighting against the Vuras, also known as the Siberians, who are the dominant gang in Site B Khayelitsha. The Vatos say that they are tired of not being able to walk freely in the streets of Site B due to the presence of the Vuras. They believe they have no other option but to fight the rival gang with the aim of killing their members as a solution to their problem. Analito says that they use knives (the okapi, which is a lock, back or slip joint knife), pangas, axes, spades, hammers or any sharp object to stab and injure or kill their rivals. They claimed they carry the okapis with them to school.

“You do get the Vatos and the Vuras in one class, but as long as the teacher is there we remain disciplined. Once that teacher leaves the class, chaos erupts. We start swearing at each other and calling each other names. Once that happens, it’s a sure thing that after school there will be trouble,” explains Abosh.

The Vatos Locos are named after a gang in the 1993 Mexican crime drama Blood In Blood Out, and the Vuras name is adopted from the Volkswagen VR6 engine. The boys explained that there are also smaller gangs emerging from these two bigger ones, with members in other townships including Gugulethu, Nyanga and Philippi.

There have been numerous reports of gangs operating in Harare, Kuyasa, Makhaza, Site B and Makhaya, with their members typically ranging from 12 to 19 years old. The violence has spread to schools, with learners being targeted on their way to and from school.

“[We are] concerned about the rise in gang violence in Khayelitsha. Young people are joining gangs in increasing numbers, and these gangs are operating in our schools and community,” says Brad Brockman, head of the youth and community department at Equal Education. He says that the gangs are assaulting and robbing young people and community members, as well as fighting against each other.

Brockman cautions that this is a complex issue: “The safety of our schools and our community is being threatened by this violence, and we need to act to change this. But let us be clear: we need to understand what is happening in our schools and community, and why young people are joining gangs. Only once we understand this and engage with these young people, can we hope to come to a long-term solution to this problem.”

Bronagh Casey, spokesperson for provincial education MEC Donald Grant, says, “As far as Khayelitsha is concerned, the Western Cape Education Department are aware of the situation and are monitoring learners’ activities closely. Together with the South African Police Services, schools have been identified and search and seizure operations have been performed.”

Casey says that there are no available statistics on the number of schools affected by the violence, but that they have received seven reports in January and February this year of gang-related activity at schools, caused by either a learner or a member of the community.

Vuyiswa Xapa, a resident from Kuyasa in Khayelitsha, says that she knows about the gang violence as it happens not only in schools but also in her area.

“The boys here in Kuyasa are fighting with boys from Harare. They are very young, some are 12 years old. I don’t know what they are exactly fighting about but I know that a lot of them have been killed already. My brother was almost attacked with a panga as well after the Vuras thought he was a Vato. There are always street meetings about how to solve this gang violence, but so far nothing has been solved and the crime is continuing,” she says.

When asked whether they feel guilty about the people they’ve killed, Latinyo replies, “No way! When you kill somebody from the opposition, you feel good because it’s minus one problem. You even go back to the members, brag and tell them not to worry because that person is no more.” Whether this is just youthful bravado or the true claims of a hardened young man is hard to know.