Chokka fishers struggle to survive in lean times

Separated for long periods from their families, the fishers eke out a meagre living catching squid

The South African squid fishery is based on a single species, Loligo reynaudii, locally referred to as chokka and also known as squid, calamari or white gold. It is found around the Agulhas Bank and West Coast shelf. South Africa exports almost all of it to Mediterranean countries such as Italy and Spain which pay more. It is a R400-million-rand industry, and in terms of employment the third most important after deep-sea hake and small pelagic fishing.

The chokka industry has dwindled in recent years, partly due to over-fishing and climate change. Regulations have been implemented to try to save the chokka population around Port Elizabeth. The regulations implemented by the SA Squid Management Industrial Association (Sasmia) close down fishing for April, May and June instead of just for five weeks in October and November. This has left thousands of fishers with no source of income during this period.

Fishers risk their lives, and there is substantial financial risk for the owners of the small boats. To supply a typical small chokka vessel for the 21 days at sea, about 3,000 litres of diesel are needed at a cost of R38,000. Together with food and all the other supplies necessary for the crew and trip, the total cost is over R60,000.

The 14-metre Santo Mersch has been a home to skipper Roy Westerdale for the past 32 years. Westerdale has two families, his family at home and his crew on the boat. Both look up to him to make the right decisions, and both depend on him for safety. His crew and family rely on him to find the chokka. He has missed many family milestones – birthdays, the festive seasons, graduations and anniversaries. 13 December 2016 was the first time he was home for his wedding anniversary – the couple’s 30th.

“Roy is out at sea for 21 days at a time and with us for three days. Roy’s home is on his boat, with his crew. When he comes home, it is only to visit,” says his wife, Lorette.

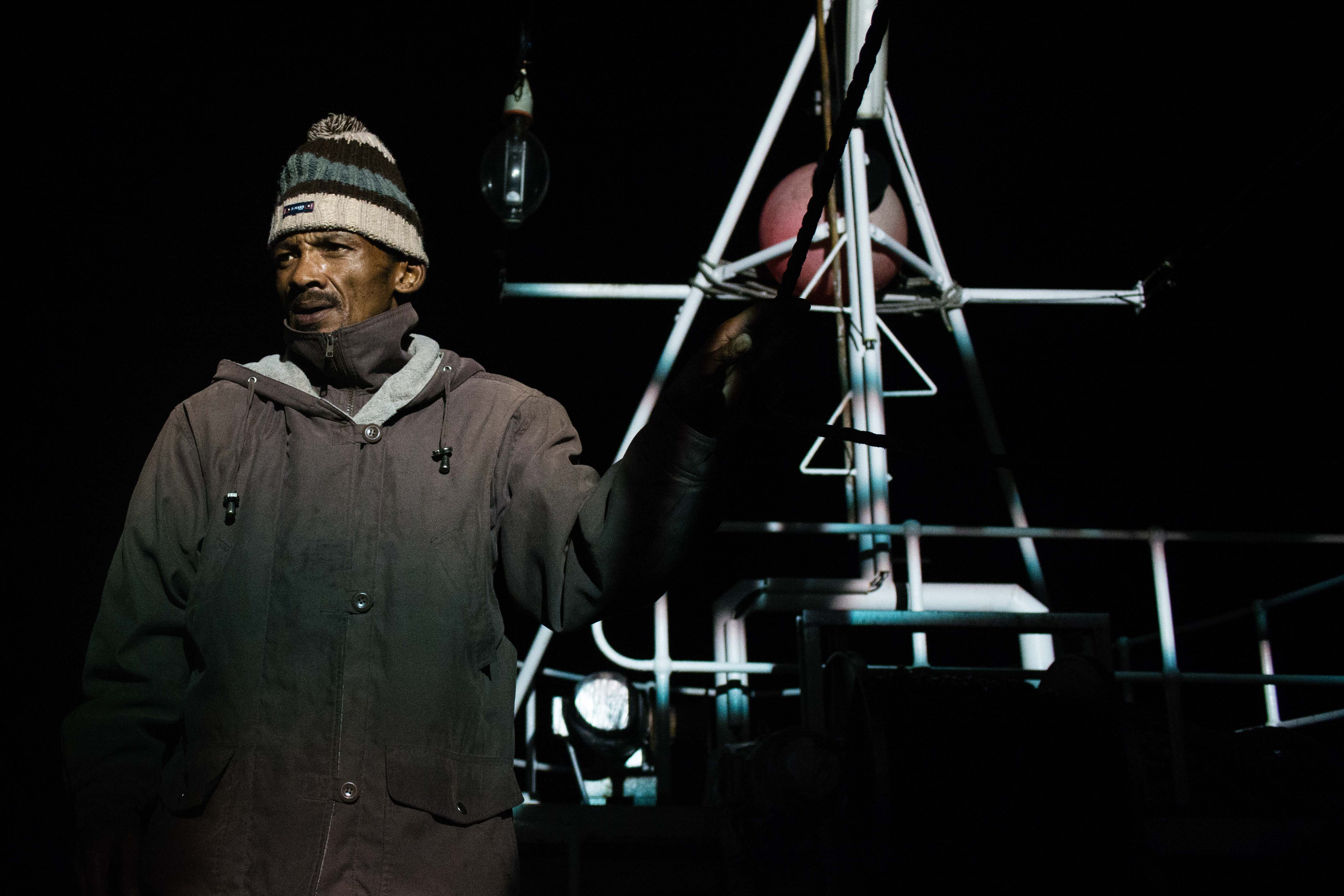

Elroy Gouda, who is 49 years old and from Port Elizabeth, has been a chokka fisherman for over 25 years. Elroy spent seven years in prison. Because of his criminal record, it is extremely hard for him to find work on land, which is why he works at sea.

“There is no work on land for me. Being in prison for seven years, the sea is the only place I can find work,” says Gouda.

Lisbie is the wife of fisherman Eric Witbooi. They have shared a home for seven years, built by her husband with recycled materials gathered from different places such as landfills and unwanted materials on building sites.

“Eric goes out to sea for three weeks where he eats and lives for free, while I am here at home with little food and no work,” says Lisbie.

Chokka fishermen do not get paid a set salary but only get paid for the amount they catch per kilogram. There is never a guarantee. Most of the time the catch is marginal and they can earn as little as R300 during a bad month. However, they can get lucky and earn up to R8,000 for three weeks of fishing.

The fishers start casting their lines when the sun begins to set and they stop as the sun rises the next morning. The catch for the evening is weighed and then they head off to their bunks to rest.

Sixteen adult men live, eat and sleep in an area no bigger than 6x6m2 for 21 days at a time. Living conditions are very tight and not very sanitary.

While the captain steers the vessel in search of chokka, the crew continuously throw their lines in, hoping the chokka bite. Most fishermen agree that there is nothing more enticing and yet enslaving than life at sea.

Themba Ngazitha, a 51-year-old from Humansdorp, has been working on chokka boats for over 20 years, supporting his wife and daughter, Patricia. His daughter has three children of her own, whom he also supports. The number of people that rely on him has caused him a great deal of stress. Thanks to support from their local church they have managed to survive, but as time goes by it is proving more difficult to make ends meet.

Palala, Ngazitha’s wife, lives in Humansdorp. “It is very difficult to know how much money Themba will be coming home with. Sometimes it is a lot and sometimes it is very little. If it is too little then I have to go buy food on credit at our local grocery store to feed all of us, hoping that from Themba’s next trip he will come home with more money,” says Palala.

Next: Ona Dubula returns home

Previous: Protests flare up again in Matatiele

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.