Role models and perseverance: how Kenny Solomon became South Africa’s first grandmaster

In December Kenny Solomon crossed the final hurdle needed to achieve what no other South African has. He won the African Individual Championship to become South Africa’s first chess grandmaster. Along the way he beat Egyptian grandmaster Ahmed Adly.

Solomon (35) grew up in Mitchell’s Plain in the 1980s, the second-youngest of eight children. His brother Graham taught him to play when he was seven years old. “I was reluctant at the time but I learnt,” recalls Solomon. It was only years later when his brother Maxwell represented South Africa at the chess olympiad —which can be thought of as the World Cup of chess— that he started taking the game seriously. He entered his first tournament when he was thirteen.

Solomon says chess kept him away from “negative influences” because he spent more time indoors and studying. “My parents were happy about this.” He says he tried to keep a low profile at his school, Lentegeur High. He was respected by his school colleagues because his chess success meant he got to travel abroad. And although chess is not the sport of jocks, he was only teased occasionally with “There goes the chess player!” I encountered him several times at chess tournaments during the 1990s, and he has always struck me as shy, but polite, friendly, and much-admired.

Competitive chess is perhaps thought of as a leisurely non-physical pursuit by non-players. But it requires extraordinary concentration for hours at a time, day after day. Walk into a chess tournament four hours into play, and it’s a picture of sweat and exhaustion. As Solomon explains, “Chess is a struggle between two intellects. This requires colossal nervous energy, focus and perseverance. My game against Adly was a very emotional one with high stakes. It lasted five hours. For such games one has to be in good physical condition and be able to recover quickly to face the next challenge the following day, maintaining the same level of play and concentration.”

In November, Magnus Carlsen from Norway beat Vishy Anand from India in the world championship. Anand, one of the greatest players in the game’s history, who held the world title from 2007 to 2013, at his best is probably as good as Carlsen, but as pundits have pointed out, he is on the wrong side of 40, and the physical ability to concentrate at the level required for top chess for hours on end, day after day, becomes elusive with age. This is arguably what separated him from Carlsen. It is why Solomon, like many top players, stays in mint physical condition. “I do running and cycling at gym, and strength training. This allows me to be able to concentrate and endure tension for five hour games,” he says.

It is hard to become a grandmaster. Chess is the world’s most popular board game. By one estimate over 600 million people play regularly, and 7.5 million are registered players, meaning at one time or another they’ve played competitively. Yet there are only about 1,450 people alive who have received the prestigious grandmaster title from FIDE, the game’s governing body. To do so you need to score two excellent performances in international tournaments competing against other grandmasters; these are known as grandmaster norms. Solomon has already scored three of these. You also need to reach a FIDE rating of 2,500, which currently would put you in about the top 900 players in the world. Although Solomon hasn’t yet done this (his rating is just shy of 2,400), by winning the African Championship he overrode this requirement. Once you get the title, you hold it for life.

In 2012, Solomon became a grandmaster-elect, meaning he had scored the required norms, but he still needed to increase his rating. Then he went through a slump. “I think Initially I put too much pressure on myself and it affected my performance,” he says. “Then I made some changes to my game which demanded most of my time as I wanted to improve in the long term. I knew that despite the negative results I was improving and deepening my understanding of the game.”

A breakthrough came beginning in April last year when he had a string of good results. Two strong tournaments were held in Pretoria and Cape Town that featured four international grandmasters, a rare privilege for South African fans. Solomon won in Pretoria and came second in Cape Town. And then he won the African Championship in Windhoek.

Solomon has dedicated himself to becoming a top player. After school he pursued chess full-time, and didn’t go to university. He settled in Venice where he lives with his wife Veronika Goi, who works in a bank, and daughter Eleonora. He makes a living as a professional player. This involves hours of daily practice following the latest developments in opening theory, improving his tactical skills, and becoming more expert in the endgame. But Solomon emphasises that he makes time for his family. Living in Europe with its abundance of chess tournaments featuring top players was the only practical way for him to become a grandmaster. I asked him if it was financially stressful playing chess full-time, but he says “As a hard-working professional chess-player it is not hard and no stress at all. At this stage of my career I am enjoying the competitive and creative process immensely.”

He explains why South Africa has not until now produced a grandmaster. “In order to play like a grandmaster you need to play often against them, to learn and gain experience. It’s not enough to play one, two or three tournaments a year in competitions where there are grandmasters. You have to play them on a regular basis. This has been the big challenge for many players from South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Botswana which are geographically far away from countries that contain grandmasters. Also chess is not marketed at the same level as sports like soccer, rugby and cricket. Sponsorships are lacking. In my case [by being in Europe] I face grandmasters on a regular basis thanks to sponsorship since 2009.”

So how do we produce more grandmasters? Solomon says, “First, players need to be educated with the correct training methods. This is where chess schools and grandmaster training plays a key role. Second, players need experience facing grandmasters in tournaments, by either sending them overseas with full support and sponsorships or creating more grandmaster tournaments in our country. For this to happen sponsorships are needed, as well as marketing and good organising. We need more volunteers and professional people.”

South Africa has actually produced many talented players who have occasionally done well internationally, but who’ve just lacked the opportunity or edge to become grandmasters. They have influenced Solomon. He says Watu Kobese from Soweto, the most prolific of the top South African players who have competed internationally, has become a good friend and taught him a lot. He was also inspired by players like “Mark Rubery, George Michelakis, Mark Levitt, David and Jonathan Gluckman, and Deon Solomons.” He also avidly read the local chess magazine published in the 1990s by Levitt.

He is grateful to the people who helped him along the way. He mentions his club chairperson Reggie Sinden, who organised a fundraiser to help cover his costs to play, many years ago, in the under 16 South African chess championships in Pretoria, which Solomon won. Cape Town players will recall Ari Snoek, an older, regular player on the chess circuit who was always formally dressed, but approachable and warm. Solomon says that Snoek read about his need for funds to get to the world youth championships. “He made a generous donation towards my trip.”

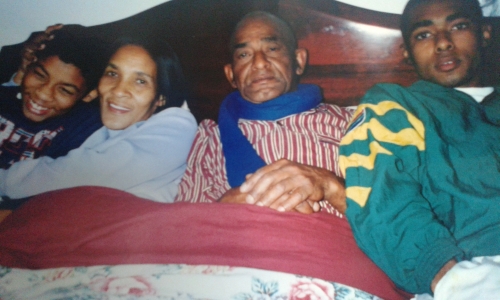

In the tough streets of Mitchell’s Plain, positive role models can make the difference between a fulfilled and a screwed up life. A big influence on Solomon’s life was his father WIlliam Charles, who died in 2011. Solomon recalls him fondly. “He worked in the Epping industrial area. He was a highly educated man and very skilled with his hands, a jack of all trades. He loved literature, history and geography. Over the years, I didn’t need to google because he would give me the detailed history and geography about the places I was visiting to play chess.”

William Charles didn’t know how to play chess, but he advised his son on the psychology of the game. He also kept abreast of chess news. “He remembered reading about Charles de Villiers, six times SA chess champion, in newspapers way back before my brothers played chess. Shortly before he passed away my dad told my mother, ‘It wont be long before Kenneth becomes Grandmaster’. He was right.”

So does Solomon want to return to South Africa? “Yes. I miss South Africa and Cape Town. Sure I would like to come back some time. There’s no place like home.”

An old family photograph. Courtesy of Kenny Solomon.

Next: Why Cape Town should not name a street after FW De Klerk

Previous: Kraaifontein gets its first spray park

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.