Rough diamonds - part one: Ten dead men

A desperate quest in a makeshift mine leads to tragedy

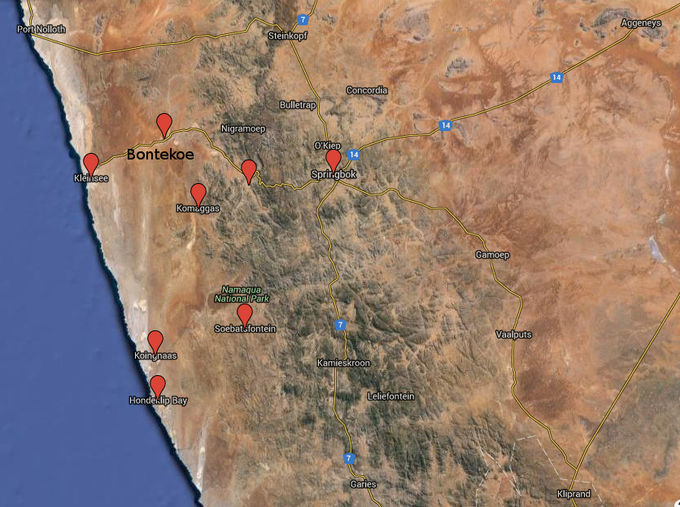

The mineshaft had been dug by hand, descending seven metres through red desert sand before widening into a circular chamber. Repurposed oil drums supported the walls. A worn ladder, held together with steel wire, led back to the surface, where more than 300 diggers waited to enter. An illicit diamond mine at the edge of disused De Beers land, 75 km west of Springbok, the site would become known as Bontekoe, the name of an adjacent mining area not owned by De Beers. It collapsed in the early hours of 22 May 2012, killing ten people.

The name of the De Beers land was Strydrivier, which translates loosely as ‘Struggle River’ or ‘Battle River’. Years had passed since it was last used for legal mining operations, but the ground was still rich in diamonds. The mine’s main chamber, termed the ‘wagkamer’ (‘waiting room’), had space for 40 people at most, squeezed tightly together. Shortly before it caved in, more than 30 diggers crouched shoulder to shoulder beneath the low dirt ceiling, sweating with their shirts off and inhaling stale air, preparing for their chance to belly-crawl into the tunnels.

The tunnels cut horizontally into the earth, following seams of diamond-bearing gravel. Some of the tunnels exceeded ten metres in length, with diameters narrowing to less than one metre. According to diggers, driven to break the law by chronic unemployment in Namaqualand, temperatures inside the tunnels reached 60 degrees Celsius. There was almost no ventilation — matches for lighting cigarettes quickly extinguished themselves once struck. There was also little structural support to withstand the pressure from tons of overlying sediment. But groups of diggers would sit in the wagkamer for more than 12 hours at a time before gaining access, after spending days waiting at the surface. The mine was exceptionally abundant, producing large diamonds on a daily basis, and diggers burrowed ever deeper in spite of the discomfort and risks.

Destined for the global luxury goods market, diamonds were the economic mainstay of Namaqualand for more than 80 years, sustaining large-scale mining operations along some 400 km of coastline — half the total length of South Africa’s west coast. But a spate of retrenchments from the 1990s onwards left hundreds of people without work, culminating in the single biggest employer in the region, De Beers, closing its mines in 2006. As a consequence of this withdrawal, informal diggers, many of whom were once mineworkers, began targeting the diamonds left behind — fuelling an illicit trade that continues across Namaqualand to this day, despite collapses like the one at Bontekoe.

Inside the mine, at the end of each tunnel, men loosened gravel with crowbars and chisels, filling 10kg maize meal sacks to sieve above ground. The dust rose in clouds, illuminated by their headlamps. It was cramped and difficult to breathe. This work continued without pause, 24 hours a day. As soon as one group exited with their sacks, another took their place. Arguments broke out frequently as rival diggers jostled for position; on occasion this sparked violence, including beatings and stabbings above ground. As word spread about the mine’s bounty, people had congregated from further and further away, spending weeks camping out in the veld or in an abandoned mining hostel nearby. The usual diggers from depressed mine towns across Namaqualand — Komaggas, Buffelsrivier, Soebatsfontein, Steinkopf, Port Nolloth — were joined by teams from Cape Town, Johannesburg, and the Eastern Cape. Everybody was chasing rough diamonds, which sell for thousands of rand per carat on the black-market, and the men who’d opened the mine up, and maintained a semblance of order at first, were losing control of the situation.

In the weeks preceding the 2012 collapse, a few diggers had started carrying jackhammers into the wagkamer, powering them with compressors left at the surface. This enabled them to remove gravel faster and access harder rock layers, but threatened the mine’s stability. Cracks began to appear in the ceiling. The earth shook intermittently as large boulders shifted. Fearing for their lives, many diggers left, warning the crowd gathered outside that the tunnels were unsafe. People jeered in response, believing that this was merely a ploy to disperse them, and continued climbing into the shaft.

Sidney*, a digger from the coastal village of Hondeklipbaai, 90 minutes drive south of Bontekoe, was one of those who chose to enter. Three diggers from Hondeklipbaai accompanied him, including Aubrey Booies, a compact, muscular man aged 35. As the group waited in the wagkamer, a dreadlocked man began pounding the roof of one tunnel with a jackhammer, raising a deafening noise. A separate group of diggers worked by hand further inside.

“The first stone fell a few minutes later,” Sidney told me when I met him in Hondeklipbaai recently. “We knew right away there was a problem. I shouted at that guy to stop using the jackhammer, because it was dangerous, but he was stubborn, and wouldn’t listen. A white dust was falling; it was like salt, or a thick mist. The guys almost choked. We couldn’t see anything.”

Though frightened, the men remained below ground. The dust settled. When their turn came, they crawled into a tunnel and removed enough gravel to fill three sacks.

“We were on our way out,” Sidney said. “I had just reached the wagkamer again. Aubrey was right next to me. The other two were a little further ahead. Then everything went dark, and the boulders started falling.”

Certain he was about to be killed, Sidney ducked and shut his eyes. Men were screaming all around him. The roar of the earth subsided. The men continued screaming. Sidney lifted his head. He was pinned on his stomach by large stones. His right hip throbbed. His mouth was full of sand. He twisted his neck to see what had happened and saw Aubrey Booies lying beside him, bleeding.

“There was blood coming from his nose, his mouth, his ears — blood everywhere,” Sidney said. “I could barely make out his face. I knew straight away that he was dead. His one hand was stretched forwards, like he was trying to reach me.”

*Name changed.

Next: Bail hearing in teen’s murder drags on for three months

Previous: ANC and the subversion of democracy: history repeats itself

© 2016 GroundUp. All rights reserved. (Note this article is not published under the Creative Commons license that we usually use.)